Weight loss is hard, confusing, and full of problems.

There are many different reasons for this, but today I want to talk about one of the biggest: your metabolism.

Or, more specifically, the fact that your metabolism slows down while you lose weight.

This fact has led to many people asking me many questions about all of the following topics:

- Metabolic Slowdown

- Adaptive Thermogenesis

- Metabolic Adaptation

- Starvation Mode

- Metabolic Damage

- Starvation Response

- Weight Loss Plateaus

In this article, I’m going to clearly explain what all of these terms actually mean, why they do (or do not) occur, what causes them, what (if anything) prevents them from happening, what fixes/reverses them once they’ve already happened, and why most of the stuff you’ve heard about your “slow metabolism” is a big stupid myth.

Let’s begin at the top of the list…

1. What Is Metabolic Slowdown?

Metabolic slowdown is an umbrella term for any decrease that your metabolic rate experiences throughout the weight loss process.

That means any factor that slows your metabolism to any extent while you lose weight – be it due to the reduction in calorie intake needed to create a deficit, or the loss of body weight experienced as a result (source) – all falls under the scope of the term “metabolic slowdown.”

It covers everything.

What kind of factors are we talking about, exactly? Here are the 5 main contributors:

- BMR decreases.

BMR is your basal metabolic rate, which is the amount of calories your body burns at rest just keeping you alive and functioning. So, imagine the number of calories you’d burn if you stayed in bed all day not moving (or digesting food). That’s your BMR, and it accounts for the majority (typically about 60% – 70%) of the calories your body burns each day. The thing is, as you lose weight, this number gradually decreases… which makes your metabolism slower. The cause of this is the simple fact that your body burns calories maintaining the organ, fat and muscle mass you have. So, the more you lose, the less you burn. Which means whatever your BMR is today, it will be something less than that after you’ve lost some weight. And it will be something less than that after you’ve lost additional weight. Basically, the less you weigh, the lower your BMR will be due to nothing more than the fact that a smaller body burns fewer calories than a larger body. - TEA decreases.

TEA stands for Thermic Effect of Activity. This represents all of the calories your body burns each day via exercise. But guess what? Since a smaller body burns fewer calories both at rest and during activity, the amount of calories you burn while exercising will gradually decrease as you gradually lose weight. So, for example, let’s say you weigh 250 lbs. Let’s also say you do some form of cardio or weight training workout and burn X calories doing so. When you get down to 200 lbs and perform that same workout for the same duration of time at the same level of intensity, you’ll now burn an amount of calories that is some degree less than X. Yet again, another factor contributing to metabolic slowdown. - TEF decreases.

TEF is the Thermic Effect of Food. This is defined as the calories your body burns during the digestion and absorption process of the foods you eat. The thing is, in order to lose weight, a caloric deficit must exist. And in order for a caloric deficit to exist, you need to eat some degree less than you were previously eating. And so less food being eaten = less calories burned via TEF. While this is much less of a contributing factor than the others on this list (it typically accounts for 10% or so of the calories your body burns each day), it’s still a small part of why your metabolism gets slower in a deficit. - NEAT decreases.

NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis) is defined as the calories burned as a result of all of the activity taking place over the course of the day BESIDES exercise (source)… which includes unconscious, spontaneous daily movement (i.e. the seemingly minor movements you make throughout the day that you didn’t consciously plan to make). So everything from brushing your teeth, to walking to your car, to typing, to shopping, to fidgeting, to adjusting your posture and much more fits into this category. NEAT actually accounts for a surprisingly significant amount of the calories that people burn each day, though it can vary quite a bit from one person to the next (source). The thing is, though, NEAT decreases when you’re in a deficit (a caloric deficit is an energy deficit, after all)… thus causing you to unintentionally (and unknowingly) move around less and burn fewer calories each day, thus contributing to the metabolic slowdown experienced. - Adaptive thermogenesis occurs.

Adaptive thermogenesis will have its own separate section in this article. We’ll get to it in a minute. But it’s another key factor slowing your metabolic rate during weight loss.

Is Metabolic Slowdown Real?

Yes, metabolic slowdown is very real.

There’s no question about it… your metabolic rate gradually slows down while you’re losing weight due to a combination of the factors listed above. It’s a real thing that really happens.

Can It Be Prevented?

Nope. The only real way you can completely prevent metabolic slowdown from happening is by not losing weight in the first place.

Otherwise, there’s nothing you can do to avoid it. Metabolic slowdown will happen to some degree to every single person who loses any amount of weight.

But at the same time, it’s not really something that’s meant to be “prevented.” This slowdown is a completely normal occurrence. It’s supposed to happen.

It may have some problematic effects in terms of making weight loss a little harder, but the slowdown itself is not actually a problem. Nor is it a sign that something is wrong with your metabolism. If anything, it’s a sign that your progress is going fine.

Can It Be Fixed?

No, because metabolic slowdown is NOT a “broken” metabolism. There is nothing that needs to be “fixed.”

This is like if a person weighed 250 lbs, then spent the next year losing 50 lbs, and then asked if their scale needs to be “fixed” because it’s now showing “200” instead of the “250” it showed a year ago.

Nope, there’s nothing broken here.

The number on the scale has simply decreased in accordance with the 50 lbs of weight loss that has taken place.

With metabolic slowdown, your metabolism has simply decreased in accordance with the five factors we discussed above.

Can It Be Minimized Or Reversed?

As for the first four factors on the list (BMR, TEA, TEF and NEAT), there’s not much you can do to minimize or reverse the decrease in metabolic rate they cause.

I mean, one way you can slightly lessen the drop in BMR is by not losing muscle mass, as your body burns more calories maintaining muscle than it does maintaining fat.

But beyond that (and ignoring the option of regaining all of the weight you’ve lost, which would technically reverse the slowdown caused by losing it), all you can really do is increase your activity level so that you burn more calories to make up the difference.

So, for example, if you lost some amount of weight over some amount of time and now burn 200 fewer calories per day than you did before, you could add in some additional exercise activity (or non-exercise activity) to burn an extra 200 calories a day.

Let me be clear though: you don’t actually have to do this.

And in most cases, continuously increasing activity to offset every decrease in metabolic rate will fall somewhere between excessive and unnecessary, and physically/mentally detrimental.

Not to mention, you can’t really outrun metabolic slowdown. The more you try to offset it with activity, the more slowdown there will be. You’ll always be playing catch-up.

Again, the fact that your metabolism gradually slows down during weight loss isn’t a problem that needs correcting. Nor is it something that warrants trying to preemptively “fix.”

Because as long as you’re in a caloric deficit (and you adjust when needed to remain in that deficit over time… more about that later), you’re going to continue losing weight just fine regardless of the metabolic slowdown taking place.

As for the 5th factor on the list (adaptive thermogenesis), let’s talk about that right now…

2. What Is Adaptive Thermogenesis?

Adaptive thermogenesis is defined as the decrease in the number of calories your body burns each day beyond what would be predicted to occur from the loss of body weight alone.

Meaning, once you factor in the expected decrease in BMR, TEA, TEF and NEAT to try to estimate how much a person’s metabolic rate should slow down after they lose a certain amount of weight, their metabolic rate will usually slow down some degree more than that predicted amount.

That extra amount of slowdown is adaptive thermogenesis.

Why Does It Happen?

It happens because the one and only thing your body cares about is your survival, and it will do everything it can to keep you alive and functioning in every condition you place it under.

In the case of weight loss, the condition you’re placing it under is a caloric deficit… which means you’re consuming fewer calories than your body needs to use for energy each day. When that happens, your body starts burning your stored fat for energy instead.

This is a good thing, because it’s what’s required for weight loss to happen.

The Survival Goal

The thing is, your body doesn’t understand that you’re only doing this temporarily so you can lose some fat, get leaner, look better, feel better and be healthier… at which point you’ll willingly end the deficit, stop losing, and just maintain this leaner, healthier, happier state from then on.

Instead, your body views all of this as you potentially being in danger of starving to death. That’s really all it sees here. It perceives your caloric deficit as an apparent lack of available food, and weight loss as you getting closer and closer to dying.

For this reason, your body adapts to your attempt at losing weight by doing everything it can to stop you from losing weight.

Adaptive thermogenesis is a prime example of just one of the ways it fights back. It’s your body slowing down your metabolic rate a little extra to conserve energy stores and lessen the amount of deficit that exists.

Is Adaptive Thermogenesis Real?

Yes, it is definitely real. It’s been seen time and time again in various weight loss studies (sources here, here, here and here).

How Significant Is It?

Here’s the part that some people get wrong about it.

You see, while this adaptive component is absolutely a real thing that really happens, it’s less significant than a lot of people think. Specifically…

So, for example, if your maintenance level should be 2000 calories after losing some amount of weight over a period of dieting, it might actually be more like 1800.

The exact amount of adaptive thermogenesis that occurs will vary from one person to the next based on factors like deficit size, deficit duration, the rate of weight loss, how much weight was lost, body fat percentage, good-old individual variance, and more.

Typically, the more extreme the case (e.g. someone who reached a very low body fat percentage, someone who lost a ton of weight, someone who’s been in a very large deficit for a very long period of time, etc.), the more adaptive thermogenesis there will be (and vice-versa).

The Myth

But regardless of whether this adaptive component ends up being 5%, 10%, 15%, 20% or something in between, it’s still less significant than many people think it is.

I know this, because I hear from people on a daily basis (literally) who are convinced that the adaptive component of metabolic slowdown has completely stopped them from losing weight. Or, in some cases, caused them to somehow start gaining weight.

And, no matter what they do… no matter how little they eat… no matter how much they burn via exercise… they can’t get back to losing weight again.

Um… no.

Adaptive thermogenesis is definitely real, but it’s not at all capable of preventing a person from losing weight or somehow causing weight gain. That’s a myth.

Hell, the participants of the infamous Minnesota Starvation Experiment – which saw adaptive thermogenesis hit about 15% (source) – kept on losing weight until they reached the lowest levels of human leanness (about 5% body fat), and the only thing stopping them from losing at that point was the fact that they’d die if they kept going.

So if adaptive thermogenesis didn’t prevent them from losing weight, it sure as shit isn’t preventing you.

What it is doing, however, is gradually slowing progress a little, gradually making weight loss a little harder than it would otherwise be, and gradually serving as one part of what requires people to have to adjust their calorie intake (and/or calorie output) over time to continue making progress.

Nothing more, nothing less.

But then you might be wondering, if adaptive thermogenesis isn’t preventing these people from losing weight “no matter what they do,” then what the hell is?

Oh, don’t worry. That’s coming up a bit later in this article. You’ll see.

Can It Be Prevented?

Nope. If you’re losing weight, this adaptation will kick in at some point.

Can It Be Fixed?

No, because it’s not something that needs to be “fixed.” Again, there is nothing broken here. Adaptive thermogenesis is part of your body’s natural survival mechanism. It’s supposed to happen.

You might not like it or want it to happen, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a completely normal occurrence that does happen.

I actually find it funny that people view this as a sign that their metabolism is broken, because it’s really the complete opposite. The fact that there are hormonal and metabolic processes taking place during a period of weight loss to help conserve energy/keep you alive is something that should be viewed as a sign that your metabolism is running smoothly and working correctly.

If that didn’t happen, only then would something potentially be “broken.”

Can It Be Minimized Or Reversed?

To some degree, yes.

- To Minimize The Effects…

This adaptation occurs as a survival mechanism, so the less “in danger” your body thinks you are, the less response there will be. So… avoid making your deficit too big (i.e. 10-25% below your maintenance level is what I consider to be ideal for most, with 30-35% being the maximum). Avoid excessive amounts of exercise, especially cardio (i.e. do the minimum needed to support your goals). Avoid being in a deficit for long periods of time without any sort of break (i.e. use refeeds, calorie cycling, and/or diet breaks to temporarily pause your deficit [sources here and here]). Avoid getting too lean (in my experience, that means less than 10% body fat for a man, and less than 18% for a woman), although this may not be possible depending on your goals. Avoid crash diets, avoid extremes, avoid “fast weight loss” (i.e. more than 1% of your total body weight lost per week), avoid stupid fads, and basically avoid doing anything that can be described as excessive or unnecessary. - To Reverse The Effects…

The only real way to reverse the adaptations that occur as a result of being in a caloric deficit and losing weight is by… no longer being in a caloric deficit and no longer losing weight. Meaning, a prolonged period of being back up to your maintenance level or in a surplus will reverse many of the metabolic and hormonal adaptations to weight loss, including adaptive thermogenesis. This can be partially achieved by using diet breaks periodically throughout the weight loss process (sources here and here), where you’d spend 1-2 weeks at your maintenance level. It can be achieved to a larger extent when you end the weight loss process itself (because you’ve reached your goal and you’re done losing), at which point you’d go back up to your maintenance level to maintain, or go into a surplus so you can either A) focus on building muscle, or B) in the case of people who have reached VERY low levels of body fat (e.g. physique competitors, people with anorexia, etc.), regain a healthy amount of body fat.

For more on the topic of adjusting every diet, exercise and lifestyle factor for the purpose of minimizing and reversing the effects of adaptive thermogenesis, metabolic slowdown in general, and everything else that sucks about losing weight, I’d highly recommend checking out my Superior Fat Loss program.

The whole thing is designed for this exact purpose, so it contains specific guidelines and recommendations for everything.

It’s here: Superior Fat Loss

Now for the next item on our list…

3. What Is Metabolic Adaptation?

Metabolic adaptation is defined as the decrease in the number of calories your body burns each day beyond what would be predicted to occur from the loss of body weight alone.

Wait.

Hold on.

Isn’t that the same thing as adaptive thermogenesis? Like literally the exact same thing?

Correct.

“Metabolic adaptation” and “adaptive thermogenesis” are two terms that can be (and often are) used to describe the exact same thing.

So, everything we just covered applies here just the same. There is no difference between them.

Adaptive thermogenesis was just the original term used in studies, so I guess it could be considered the more technical of the two? And metabolic adaptation could maybe then be considered the more mainstream-friendly of the two? Who knows.

Either way, they’re the same thing. So, feel free to use whichever you like best.

But Use It Correctly!

Please note, however, that if you or someone else is using the term “metabolic adaptation” to describe anything besides what adaptive thermogenesis is… that’s incorrect.

I bring this up because I see it happen all the time, most often by people using it in place of “starvation mode” or “metabolic damage.”

As if these are all just interchangeable terms that refer to the same thing.

They aren’t. And they don’t.

And no, I’m not just nitpicking semantics here. Nor am I being “the grammar police.”

Different words mean different things. And as you’ll see in a minute, starvation mode and metabolic damage are VERY different from what metabolic adaptation is.

So if you’re using one to describe the other, you’ll be communicating something very different than you think you are.

Speaking of which…

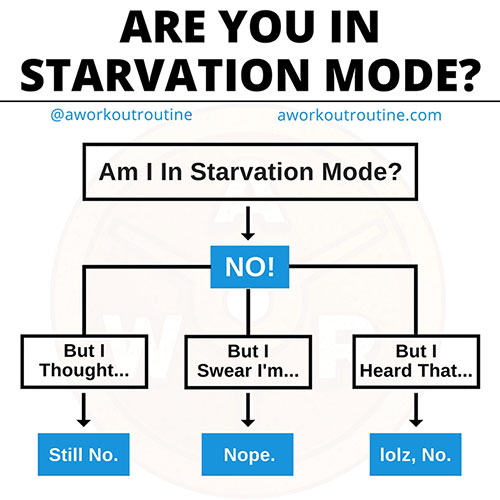

4. What Is Starvation Mode?

Starvation mode is the (nonexistent) state a person thinks they are in when they stop losing fat because they’re “not eating enough” and are therefore in TOO MUCH of a caloric deficit.

Basically, they are eating too little and/or burning too much and their deficit is too large, and so their body’s survival response is to hold on to all of their fat, prevent them from losing anything, and sometimes even cause them to gain additional fat… all despite being in a caloric deficit and “doing everything right.”

Many consider it a sign that adaptive thermogenesis has kicked in extra hard, or that significant metabolic damage has taken place and some aspect of their metabolism is now broken.

And thus, they aren’t losing fat even though they’re in a deficit.

Is Starvation Mode Real?

No.

Not at all.

Not even a little.

Not for anyone… under any circumstance… ever.

Starvation mode is complete and utter bullshit. It doesn’t exist. It’s a myth.

Did I make that clear enough? No? Let me try again…

All clear now? Good. 🙂

The truth is, a caloric deficit (regardless of how big it may be) will ALWAYS work.

There are no exceptions to this fact. The laws of thermodynamics always apply to everyone. Yes, even under the most extreme circumstances.

For example…

- People with anorexia reach deathly skinny levels by starving themselves.

- Starving children in Africa reach deathly skinny levels due to not having enough food.

- People in concentration camps reached deathly skinny levels from being starved.

- Reality show contestants on shows like Survivor or Naked And Afraid lose a ton of weight from being unable to eat enough.

- The participants of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment continuously lost fat by eating less and less until they reached dangerously low levels of body fat and essentially had no more fat left to lose.

- Every single well designed calorie-controlled study shows fat loss happens every time a caloric deficit is present, regardless of the size of the deficit or the manner in which it was created.

So why isn’t starvation mode happening in any of these scenarios? Why did all of these people lose a shitload weight when they “didn’t eat enough?” Why didn’t starvation mode stop any of them from losing anything?

Because starvation mode isn’t real.

To quote myself from a previous article…

As long as you create a caloric deficit (meaning consume fewer calories than your body burns, or burn more calories than you consume… just different ways of saying the same thing), then you will lose weight every single time regardless of whether you’re creating a deficit that is small, moderate or large.

Even if your calorie intake is dangerously low (not recommended at all, just making a point), you will still lose weight.

There is no such thing as “I’m not losing any weight because I’m eating too little.” That’s horseshit. And there’s definitely no such thing as “I’m gaining weight because I’m eating too little.” That’s even bigger horseshit that I can only assume would require the presence of an even bigger horse.

And the idea that you skipped breakfast or waited longer than 3 hours between meals (or something equally meaningless) and have now instantly entered starvation mode as a result is too laughable to even warrant another second of discussion.

Create a consistent deficit and weight loss will happen. Calories in vs calories out always applies, no matter how low the “calories in” part is (or really, how low you mistakenly think it is).

But wait, what’s that you say?

Doesn’t the body do everything it can do to keep you alive? Didn’t I just say that before?

Yup.

So doesn’t it hold on to your fat when you’re not eating enough… to keep you alive?

Nope.

It actually does the complete opposite.

The primary reason your body stores fat is so there will be a backup fuel source available to burn to provide the energy needed to keep you alive in case a situation ever arises where you don’t have access to food and your survival may be in jeopardy.

Meaning, your body stores fat for the specific purpose of burning it when you’re “not eating enough” (aka… in a consistent caloric deficit).

Which means burning fat while in a deficit IS the survival mechanism.

Not the other way around.

For more on what is easily one of the dumbest myths of all time, check out my complete guide here: The Starvation Mode Myth

Now for the next obvious question…

Why Aren’t People Losing Weight While In A Caloric Deficit?

If it’s not starvation mode, and, as we learned earlier, adaptive thermogenesis is nowhere near significant enough to make this happen, then what exactly is the problem here?

Why are so many people who are in a caloric deficit not losing weight… even though they’re doing everything right?

It’s quite simple: they aren’t actually doing everything right.

Taaadaaa!

And what it ALWAYS comes down to is the guaranteed fact that one or more of the following mistakes are unknowingly being made:

- You’re not actually in a caloric deficit.

You’re unknowingly eating more than you think you are, burning less than you think you are, or some combination of the two, and no deficit actually exists. This is seen constantly, especially among people who “swear” they are eating some really low amount of calories and “promise” they are in a deficit. They are wrong, and this has been supported by countless real-world examples and a variety of studies (sources: here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). Above all else, the #1 reason why a person isn’t losing weight in a deficit is that they aren’t in a deficit. Simple as that. - Your “weight” is being temporarily counterbalanced.

In this case, you are in a deficit and you are successfully losing body fat, but you’re simultaneously gaining some other form of “weight” that temporarily counterbalances it and temporarily prevents any progress from showing up on the scale. So, you might lose X pounds of fat while gaining X pounds of something else (i.e. water, muscle, glycogen, poop, food, etc.), thus causing your weight to temporarily stay the same or sometimes even go up. (Details here: The Weight You Gain In One Day Or Week Isn’t Fat) - You’re not properly tracking your progress.

This is another case where you’re successfully losing body fat, only… you don’t actually realize it. How can that be? Because you’re either A) not accurately measuring your progress, B) not accurately interpreting your progress (or lack thereof), or C) a combination of both… and it’s preventing you from seeing that it’s happening. So, fat loss is taking place like it should be… you’ve just incorrectly concluded that it isn’t.

These are the three real categories of problems for what’s really happening every single time a person incorrectly concludes they’ve entered the imaginary state of starvation mode.

To learn every possible cause for each of these three problems (and the solutions to them), check out the most comprehensive guide you will ever find: Why Am I Not Losing Weight? 36 Possible Reasons

Can It Be Prevented, Fixed, Minimized Or Reversed?

No, because starvation mode doesn’t exist in the first place.

One More Thing…

And if you insist on using the term “starvation mode” – something that isn’t real – to refer to adaptive thermogenesis/metabolic adaptation – something that is real – you’re doing it wrong.

Different words mean different things.

Use them correctly.

Moving on…

5. What Is Metabolic Damage?

Metabolic damage is the (nonexistent) side effect some people think they experience while losing weight (and/or after losing weight) that involves some sort of permanent damage being done to their metabolism that makes it slower from that point on, thereby making it significantly harder (or even impossible) for them to lose additional weight, or causing them to regain the weight after they lose it.

Supposed causes of metabolic damage include:

- Losing too much weight.

- Losing weight too fast.

- Constant yo-yo dieting (losing weight, gaining it back, losing it again, gaining it back, etc. over a span of months/years/decades.)

- Getting too lean (like a physique competitor needs to for a competition).

- Getting too skinny (like someone with anorexia might unfortunately do).

- Being on a very low calorie diet/crash dieting.

- Skipping a meal, or going too long without eating.

- Doing too much cardio.

- Being in “starvation mode” for too long.

Basically… losing weight, the manner in which you lost weight, or something you did while losing weight has broken some aspect of your metabolism and damaged it permanently.

As a result of this damage, you’re now left with a metabolic rate that is permanently slower than it should be, and that’s what’s making it hard/impossible for you to lose weight (or avoid gaining the weight back after losing it).

Is Metabolic Damage Real?

No, it’s not.

As we’ve already covered, your metabolic rate gradually slows down over time while losing weight.

This is a very real thing (aka, metabolic slowdown), and it occurs primarily due to a combination of:

- The fact that you’ve lost weight, and a smaller body burns fewer calories.

- Adaptive thermogenesis.

However, none of this is “damage.”

These are completely normal occurrences that are supposed to happen, and they happen to everyone who loses weight.

“But I Can’t Lose Weight No Matter What I Do! It’s Because My Metabolism Is Damaged!”

Nope.

The idea that you’re unable to lose weight despite being in a caloric deficit isn’t a sign that your metabolism is damaged. It’s a sign that you’re not actually in a caloric deficit.

In fact, one study looked specifically at people who claimed to be unable to lose weight even though they were supposedly eating less than 1200 calories a day. They assumed it was because some aspect of their metabolism was damaged, but what the study actually found was that they were eating an average of 47% more calories per day than they thought/claimed.

So, yeah… this is the same starvation mode nonsense we covered earlier. Feel free to read it again to see the REAL reasons why you’re not losing in this scenario.

“What About Metabolic Damage Caused By Getting VERY Lean?”

Nope.

Even in cases when a person has reached an extremely low level of body fat – a level that the majority of people reading this will never actually reach – there is still no sign of there being some sort of permanent, damage-induced metabolic slowdown that persists afterwards.

In fact, one research paper looked at everything from the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, to studies done on people with anorexia, to studies done on bodybuilders/physique competitors, and it concluded that the concept of metabolic damage is nothing more than a myth…

The findings here show that human metabolism is highly plastic and rapidly adapts to changes in energy availability and body composition. This stands in contrast to the hypothesis of an inflexible metabolism that is susceptible to metabolic damage during prolonged caloric restriction. As such, the presence of metabolic damage in non-obese individuals is not supported by the current literature.

“What About Damage Caused By Constant Yo-Yo Dieting?”

Nope.

Here’s a study that looked specifically at women who have lost weight and gained it back at least three different times in their lives, and there were no signs of any “metabolic damage” or anything that made it any harder for those women to lose weight again.

In fact, compared to women who had never yo-yo dieted before, there were no significant differences whatsoever in terms of fat loss results. Simply put, losing weight and gaining it back over and over again didn’t affect anyone’s ability to lose weight the next time they attempted to do so. Not even a little.

Similar studies show the exact same thing (sources here and here).

And here’s another study showing that metabolic changes during the weight loss process don’t lead to regaining the weight after losing it.

“What About ‘The Biggest Loser’ Study? That Shows Damage!!”

Ah yes, the one study that kinda, sorta, almost, maybe, supposedly appears to show that metabolic damage is a real thing.

If you’re not familiar with it, let me give you a quick recap of what it showed.

Actually, scratch that. Let me give you a quick recap of the media coverage it got and what most people ended up taking away from it:

- Many of the contestants on the reality show, The Biggest Loser, regained most (if not all) of the weight they lost on the show.

- Their metabolisms were measured 6 years after being on the show and were found to be significantly slower than they should be, even after they regained most/all of the weight back.

- This is proof that permanent metabolic damage is real.

- The reason why they regained the weight they lost is because of this permanent metabolic damage.

- Everyone who loses weight will end up damaging their metabolism and regaining the weight they lose.

- Weight loss is, therefore, a hopeless endeavor.

Ehhh… not quite.

As with any study that people don’t actually read and instead learn about second-hand (or third-hand) via clickbait headlines from mainstream sources written by people who don’t understand the subject they’re writing about, there are a few important things being missed here, and a few issues with the study in general.

Here are the four I think are most important…

1. Is This Study Even Relevant To The Rest Of Us?

Honestly? Probably not. At least, not entirely.

This was a study done on a very specific group of people who were in a weight loss scenario that 99.9% of us will never come close to being in.

- For starters, these were morbidly obese men and women. They each started, on average, at a weight over 300 lbs. And they each lost, on average, over 100 lbs. In just 30 weeks! Hell, one guy went from 430 lbs to 191 lbs (239 lbs lost). In… 30… effing… weeks.

- And much more importantly, they made this extreme progress in the most extreme (and stupid) manner possible. These were people who were put on diets consisting of close to 1000 calories a day (I’ve read reports of people eating even less than that on the show) WHILE doing up to 6 or 7 hours of intense exercise per day. For… 30… weeks.

Now… does ALL of the above describe you and the manner in which you’re losing weight?

No?

Good, because this show is terrible, the “coaches” are terrible, and every single aspect of the way its contestants approach weight loss is terrible.

But getting back to my point here, the fact that this weight loss scenario isn’t entirely (or even remotely close to being) relevant to you makes it very likely that the outcome of the study may not be entirely relevant to you, either.

That’s not to say it should therefore be ignored, or that there’s nothing useful here, or that some aspect of it can’t be applied to someone in a less extreme/stupid weight loss scenario. It’s just to say that this shit isn’t normal and it does not represent anything close to typical. So… maybe you shouldn’t assume that the same outcome seen here is the same outcome that would be seen with you. Because it isn’t.

2. This Is One Study. The Overwhelming Body Of Research Shows The Opposite.

This is one study… of just 14 people… in one very specific and very extreme weight loss scenario… that potentially supports the concept of “permanent metabolic damage” being a thing.

Cool.

But there are dozens of studies involving significantly more people in a much wider variety of weight loss scenarios that do not support it, and instead serve as solid evidence that permanent metabolic damage isn’t a thing.

Again, this doesn’t mean you should ignore this study. It just means you shouldn’t point to it and say “See!! Metabolic Damage is real!!!” while ignoring the much larger body of evidence that shows the opposite. Because, logically, the side with the larger body of evidence tends to be the side that’s right.

3. The Study Has Some Flaws

Look, I love a good study as much as the next nerd, but one thing that quickly becomes apparent to anyone who reads studies on a regular basis is that most are flawed or limited in some way, and sometimes it’s to a degree that has a meaningful impact on its results or the conclusions you should take from it.

In terms of this “Biggest Loser” study, here’s a quote from published scientist James Krieger on some of its issues…

Those of you who saw my recent presentation in the UK may remember me discussing the measurement of RMR, and why it is absolutely critical that subjects are weight stable when you measure it. RMR is very sensitive to energy surpluses or deficits, and can give an illusion of being higher or lower than normal if your subjects are not truly weight stable. If you look at the data in the Biggest Loser study, you will see that the researchers had the subjects weigh themselves daily at home on a scale that transmitted data back to the researchers. They had 16 days of data, and used statistical regression to see if weight was stable over that time. Basically, they looked at if the slope of the line was different from 0 (a flat line). It was not significantly different from 0. However, the kicker is that the P value was quite low at 0.1, which is not far from being statistically significant (which is considered at 0.05 or less). The thing is, statistical significance is nothing more than an arbitrary threshold, and with small sample sizes like in this study, you can often mistakenly call things “not different” when they are (a type II error).

On average, the subjects were losing 0.5 pound per week. Yeah, it’s not large, it may have not met the threshold for statistical significance, but this data doesn’t give me much confidence that the subjects were weight stable. It tells me the subjects may have been in an energy deficit when they were measured, which would make RMR appear artificially lower than it really is.

The other thing is that this study is at odds with other research in this area, which has shown that downregulation of NEAT/spontaneous activity is much greater than adaptations in RMR with weight loss. The Biggest Loser study showed no downregulation of physical activity, yet a large reduction in RMR. That makes me suspect that the subjects, knowing they were going to be measured in a follow-up, were actively trying to lose weight and exercising heading into the follow-up. This would explain the lower RMR (because they were in a deficit), yet the lack of reduction in physical activity (because they were exercising).

I’ve always considered the data out of Rudolph Leibel’s lab to the “gold standard” in this area, because he has subjects housed in metabolic wards for long periods of time, matches subjects to controls, and uses formula diets to meticulously control their calorie intake and ensure weight stability. Leibel’s work has shown only minor reductions in RMR, with most of the adaptation occuring in NEAT/SPA. Unfortunately, Leibel has never had subjects with such large scale weight losses as the Biggest Loser, so it’s still possible that extreme losses will result in more extreme adaptation. Still, I don’t think the adaptation is as high as what is being reported in this study, due to the limitations discussed here.

The thing is, even with the large reduction in RMR, total daily energy expenditure did not show any signs of adaptation, and TDEE is what really matters anyway, not RMR. (source)

This matters. A lot.

4. It’s Still Not Why They Regained The Weight

Even if you ignore all of the above (and you definitely shouldn’t ignore all of the above, because it changes things quite a bit), the fact remains that a “damaged metabolism” still isn’t the reason why these people regained the weight they lost.

They regained that weight for one of the most common reasons anyone regains the weight after they lose it: because they lost it in a manner that wasn’t sustainable.

And in this particular case, you can multiply that by about a billion.

The people on this idiotic show lost weight in the dumbest, most extreme, and most unsustainable way imaginable. They didn’t learn anything. They didn’t develop any important dietary or behavioral skills. They didn’t create the necessary habits required for long-term success.

And then they suddenly leave the isolation of the fake reality show world they’ve been living in and return to the real world without a clue how to maintain the extreme weight loss they just experienced.

And so… they don’t.

This isn’t rocket science, folks.

And it sure as shit doesn’t have a single thing to do with any supposed “metabolic damage.”

It’s just a bunch of people who lost hundreds of pounds stupidly fast for a TV show without doing a single thing that’s conducive to keeping that weight off afterwards. Simple as that.

Really, if there is anything anyone should ever take away from The Biggest Loser or any studies involving it, it’s that the way people on The Biggest Loser approach weight loss is a perfect example of what not to do.

“Why Do So Many People Tell Me I’m Not Losing Weight Because I Need To Repair My Broken Metabolism?”

Because those people are either:

- Wrong.

- Misinformed.

- Stupid.

- Trying to sell you some kind of diet, workout, supplement or magical “slow metabolism cure” to “repair your broken metabolism” and solve a problem that doesn’t actually exist.

- All of the above.

“But Aren’t There Real Metabolic Problems?”

Yup.

There are definitely real health issues that negatively affect metabolic rate. However, this is completely different from what we’re talking about in this article.

For example, hypothyroidism is a real condition that results in a slower metabolism.

But… this still isn’t “metabolic damage.” It also isn’t a “broken metabolism.” And it’s not something that happened because of the weight loss you’ve experienced or the manner in which you lost that weight.

It’s a legitimate medical condition with legitimate causes that requires a legitimate medical diagnosis and intervention (from a legitimate doctor) to treat.

Still… isn’t… metabolic damage. That’s not real.

(Note: If you think you have a legitimate underlying/untreated medical condition that’s affecting your metabolism (such as hypothyroidism) – and especially if you have other symptoms present – then by all means feel free to get checked out by a doctor. It’s the only way to know for sure, and the only way to treat it.)

Can It Be Prevented, Fixed, Minimized Or Reversed?

No, because metabolic damage isn’t real.

One More Thing…

Just one more reminder than different words mean different things.

So, just like with “starvation mode,” if you’re using “metabolic damage” to refer to “metabolic adaptation” or “adaptive thermogenesis,” you’re doing it wrong.

Next…

6. What Is The Starvation Response?

The starvation response is an umbrella term for all of the ways the human body fights back against weight loss.

Like I explained earlier, the only thing your body cares about is keeping you alive. And since it can’t tell the difference between you eating less/losing weight so you can look and feel better, and you eating less/losing weight because you’re about to starve to death, it responds the same way in both cases.

And that is by doing everything it can to stop it from happening. For example:

- Adaptive thermogenesis/metabolic adaptation occur.

- Hunger and appetite increase.

- Awareness of food increases.

- NEAT decreases.

- Lethargy increases.

- Leptin decreases.

- Ghrelin increases.

- Thyroid decreases.

- Testosterone decreases.

- Cortisol increases.

- Sleep quality decreases.

- Energy spent on unessential things decreases.

- Muscle loss increases.

- Strength, performance and recovery decreases.

- Libido decreases.

- Sexual function decreases.

- Reproductive function decreases.

- And more.

(For a full breakdown of every item on this list (why they happen, how to minimize/reverse it, etc.), check out Superior Fat Loss. I cover all of it in there.)

And this all happens as part of, or as a result of, the starvation response.

It’s your body doing everything it can to either get you to eat more calories or conserve energy so you burn fewer calories.

So, yeah… you’re purposely trying to eat less and burn more to lose weight, and your body is trying to get you to do the complete opposite.

That’s the starvation response.

Is The Starvation Response Real?

Yes, it’s definitely real.

It’s key to the survival and evolution of humans as a species. We wouldn’t exist today without it.

It’s also a major part of why weight loss is so damn hard: your body is purposely trying to make it that way.

Can It Be Prevented?

Nope. Just like with all aspects of metabolic slowdown (including adaptive thermogenesis), the only way you can truly prevent this response is by not losing weight in the first place. Otherwise, it’s going to kick in at some point.

Can It Be Fixed?

No. Yet again, it’s not something that needs “fixing.”

It’s supposed to happen.

Can It Be Minimized Or Reversed?

To some degree, yes.

And it’s largely about doing the same stuff we discussed earlier…

- To Minimize The Effects…

This adaptation occurs as a survival mechanism, so the less “in danger” your body thinks you are, the less response there will be. So… avoid making your deficit too big (i.e. 10-25% below your maintenance level is what I consider to be ideal for most, with 30-35% being the maximum). Avoid excessive amounts of exercise, especially cardio (i.e. do the minimum needed to support your goals). Avoid being in a deficit for long periods of time without any sort of break (i.e. use refeeds, calorie cycling, and/or diet breaks to temporarily pause your deficit [sources here and here]). Avoid getting too lean (in my experience, that means less than 10% body fat for a man, and less than 18% for a woman), although this may not be possible depending on your goals. Avoid crash diets, avoid extremes, avoid “fast weight loss” (i.e. more than 1% of your total body weight lost per week), avoid stupid fads, and basically avoid doing anything that can be described as excessive or unnecessary. - To Reverse The Effects…

The only real way to reverse the starvation response is by no longer being in a caloric deficit and no longer losing weight. Meaning, a prolonged period of being back up to your maintenance level or in a surplus will reverse many of the metabolic and hormonal adaptations to weight loss (like everything on the list from before). This can be partially achieved by using diet breaks periodically throughout the weight loss process (sources here and here), where you’d spend 1-2 weeks at your maintenance level. It can be achieved to a larger extent when you end the weight loss process itself (because you’ve reached your goal and you’re done losing), at which point you’d go back up to your maintenance level to maintain, or go into a surplus so you can either A) focus on building muscle, or B) in the case of people who have reached VERY low levels of body fat (e.g. physique competitors, people with anorexia, etc.), regain a healthy amount of body fat.

Once again, I created Superior Fat Loss with the starvation response in mind. It’s designed from top to bottom to minimize/reverse its effects as much as realistically possible.

Last but not least…

7. What Is A Weight Loss Plateau?

A weight loss plateau is what happens when progress stalls and you stop losing weight after a period of successfully losing weight.

So, everything is going well, there’s fairly consistent progress for some number of weeks or months, and then… it stops.

Sometimes it’s a gradual thing. For example, maybe you were consistently losing 1 lb per week for a bit, but then started losing 0.75 lb per week, followed by 0.5 lb, then 0.25 lb, and then… nothing at all.

Other times, you may go from consistently losing 1 lb per week for many weeks to suddenly losing nothing the very next week.

Are Weight Loss Plateaus Real?

Yes, they definitely are.

They happen all the time due to one or more on the following reasons:

- Known noncompliance.

This is when you stop losing weight as a result of NOT doing what needs to be done with your diet and/or workout. And you know it. So, maybe you’ve been eating poorly, missing workouts, not being consistent, losing motivation… that kind of thing. Whatever the reason may be, you know you’re not in a caloric deficit anymore, and that’s why weight loss progress has stopped. - Unknown noncompliance.

This is the same as above – you’re no longer in a caloric deficit – only in this case, you don’t actually realize it. Rather, you’re unknowingly eating more and/or burning less than you’re supposed to be/think you are (details here: Why Am I Not Losing Weight), and a deficit doesn’t exist. And no deficit = no weight loss. - Your “weight” is being counterbalanced.

This is the same thing we covered earlier. You are in a deficit and you are successfully losing body fat, but you’re simultaneously gaining some other form of “weight” that temporarily counterbalances it and temporarily prevents any progress from showing up on the scale. So what you really have here is a temporary weight loss plateau, not a fat loss plateau. (Details here: The Weight You Gain In One Day Or Week Isn’t Fat) - You’re not properly tracking your progress.

Here’s another one we covered earlier. You’re successfully losing body fat, but you don’t realize it because you’re not accurately tracking or interpreting your progress. You just incorrectly think you’ve stalled. - A “True Plateau” has occurred.

And finally, we have what I like to call a True Plateau. In the previous 4 scenarios, you have a plateau that came about due a mistake being made on your part. Whether it’s confusing a weight loss plateau with a fat loss plateau, improperly tracking/interpreting your progress, or not being in a deficit due to some form of known or unknown noncompliance… these are all examples of “False Plateaus.” A True Plateau, on the other hand, is when progress stops on its own even though you WERE in a deficit. Only now… your previous weight-loss-causing deficit has become your new weight-loss-stopping maintenance level. Basically, all of the real components of metabolic slowdown (BMR, TEA, TEF, NEAT, adaptive thermogenesis) have come together to gradually lower your metabolic rate enough to wipe out the deficit you initially had when you weighed more. Which means, a deficit no longer exists… which means fat loss stops happening.

Can It Be Prevented?

Technically, yes. Although, the prevention method depends on the cause.

- If it’s a plateau caused by known or unknown noncompliance, the obvious way to prevent it is by staying compliant with your diet and training. Duh.

- If it’s really just a temporary weight loss plateau that’s temporarily hiding your fat loss progress, you can’t really prevent it, as normal weight fluctuations like this are bound to happen. But, being more patient, being aware that this sort of thing can (and often does) happen, and giving it more time (based on my experience, I recommend 3-4 weeks) before assuming it’s a True Plateau would help prevent you from making this mistake in the first place.

- If it’s improper tracking that’s making you think progress has stopped even though it hasn’t, ensuring that you’re tracking as accurately as possible would help prevent this mistake from being made (details here: When And How Often To Weigh Yourself)

- And if it’s a True Plateau caused by metabolic slowdown, you could continuously lower your calorie intake (or increase your calorie output) every time you lose a certain amount of weight (e.g. every 5 lbs), this way you’ll offset some of the metabolic slowdown taking place and (hypothetically) always remain in some degree of a deficit… which means fat loss progress should (hypothetically) never come to a complete stop. However, I don’t actually recommend trying to do this. You’ll mostly just end up driving yourself insane for reasons I explain here: When Should I Recalculate My Calorie Intake And Adjust My Diet?

So, yes, I’d highly recommend trying to prevent False Plateaus.

But True Plateaus? Not really. Instead, I recommend waiting for them to eventually happen, and then simply adjusting at that point to get back to making progress again.

Can A True Plateau Be Fixed?

Just in case it needs to be said again, there is nothing here that’s broken or in need of fixing.

True weight loss plateaus are a completely normal and completely temporary pause in progress that comes about for very simple reasons. They should be expected to happen at some point, and sometimes multiple points depending on how much weight a person needs to lose.

Don’t think of it as an obstacle in your way that’s preventing you from reaching your goals. It’s not. It’s just a natural occurrence on the way to reaching those goals.

Think of it as a mile marker… not a hurdle.

Can A True Plateau Be Minimized Or Reversed?

Minimized? To some degree… yes. See the suggestions given earlier in this article for minimizing adaptive thermogenesis and metabolic slowdown in general. Any beneficial impact you have in that regard will (slightly) lessen how often a True Plateau occurs and/or (slightly) delay its occurrence.

Reversed? That’s not really the right term to use in this context. “Broken through” is more common, but it’s so over-dramatic.

I much rather phrase it as simply “getting back to losing weight again.”

As in, can you get back to losing weight again after reaching a True Plateau? The answer is yes.

And it’s really, really, really simple. Here’s how:

Taaadaaa!

That’s literally all it takes.

Remember, a True Plateau occurs because your metabolism slowed down enough over time (due to the real factors that cause metabolic slowdown) to wipe out the initial deficit you had. And so, the super complicated solution that “breaks through” this plateau and gets progress happening again is by creating a deficit once again.

Simple as that.

Summing It All Up

So, what did we learn here today? All sorts of stuff.

Rather than trying to summarize everything, here are a few of the most important points:

- Metabolic slowdown is real. It happens due to a combination of the fact that a smaller body burns fewer calories + an adaptive component.

- Adaptive thermogenesis is real, and it’s the adaptive component of metabolic slowdown. It’s no where near significant enough to prevent fat loss (or somehow cause fat gain). It’s just a factor that makes weight loss a little harder/slower than it would otherwise be.

- Metabolic adaptation is real, and it’s the exact same thing as adaptive thermogenesis. Just two terms that can be used to refer to the same thing.

- Starvation mode is a myth. And a really stupid one.

- Metabolic damage is a myth. No aspect of what slows your metabolism during/after weight loss is “damage.” Nor is there anything that “permanently” makes you incapable of losing weight or keeping it off after you lose it.

- The starvation response is real, and adaptive thermogenesis/metabolic adaptation is one component of it.

- Weight loss plateaus are real, and they can occur for a variety of reasons. A True Plateau, however, occurs because enough metabolic slowdown took place over time to wipe out your initial deficit. Eating a little less/burning a little more will create a new deficit, at which point progress will start happening again.

- Your metabolism isn’t broken or damaged. Nothing needs to be fixed or repaired.

- A deficit always works.

- If you’re not losing weight despite doing everything right, you’re not actually doing everything right.

- Different words mean different things. Use them correctly.

The End.

What’s Next?

If you liked this article, you’ll also like: